As our second consecutive season of enormous wildfires winds down, the recovery is underway. Alongside foresters, range experts, road and bridge builders, archaeologists are combing the landscape and literally picking up the pieces left behind after the blazes.

In most of BC, we’ve been fortunate not to lose many homes or buildings, but the fire’s impact to the land itself is substantial: vast tracts of forest burned to nothing have left bare slopes and loose silt. Fencelines that defined cattle ranges are gone. Fireguards and ad hoc roads made in the effort to contain the fires have also scarred the land.

The work of stabilizing slopes, rebuilding fences, reclaiming fireguards is just beginning. In all of these settings, archaeological sites long hidden under the surface have been exposed, and the scientific information and cultural knowledge contained in these sensitive and finite cultural resources are at risk.

In archaeology, fire recovery is considered in two main areas: the impacts caused by fires themselves, and the often much more serious damage caused by the heavy machinery used to fight the fires.

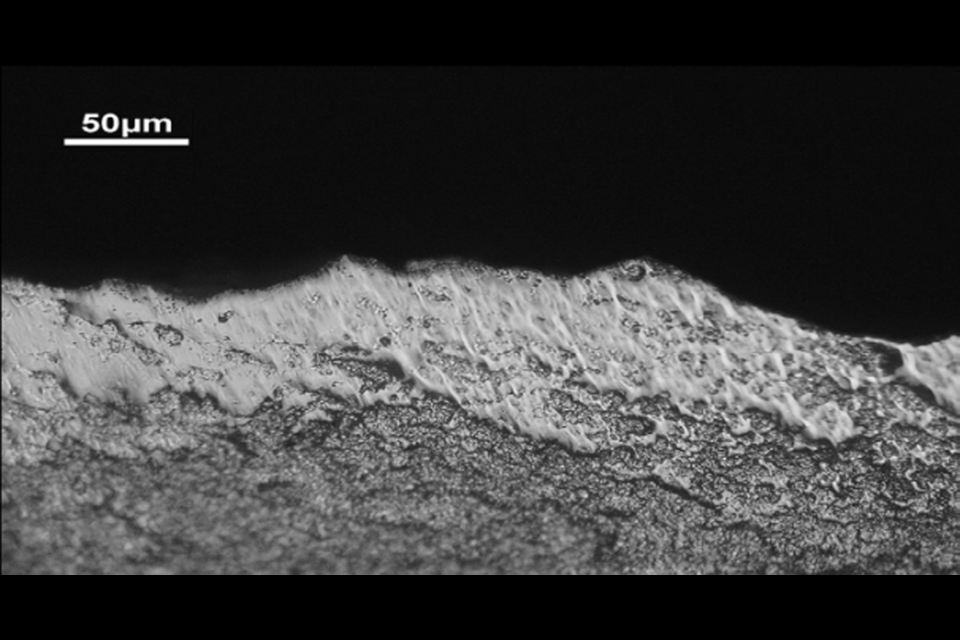

Impacts to sites from the fires generally includes destabilizing site deposits, as ground cover, tree roots, and organic layers that have protected buried sites are burned off. This means that sites long held in place under forests are now exposed, and at risk of literally slipping away.

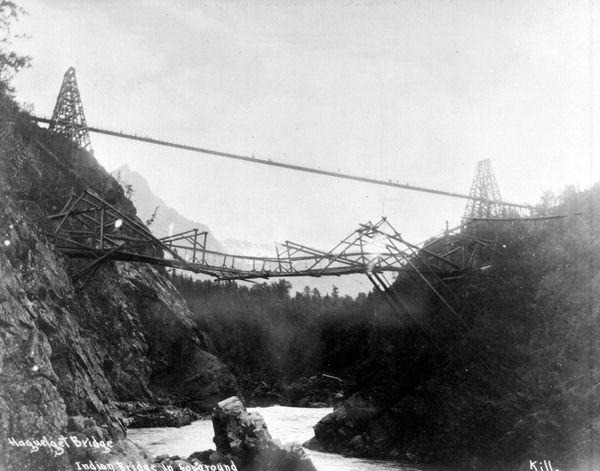

Severe mechanical damage is caused to sites by plowing through forested landscapes to create breaks, helipads, and staging areas. Features like housepits and earth ovens are easily destroyed and artifacts can be broken and displaced.

In the southern interior, caring for these remains in the wake of the fires has become a cooperative project of local First Nations, archaeologists, and Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.

As you read this, archaeologists and Indigenous field technicians are surveying the fire zones, recording new sites and assessing damage to known ones. This triage work will continue through the fall, and into next year, as we decide which sites need attention and what, if anything, we can do to preserve their value.

Fireguards in particular are providing an exciting opportunity to get a glimpse at terrain we’ve seldom had a chance to see. Fireguards are a swathe of ground about a tree length wide plowed around a fire’s perimeter in an effort to contain it, and they’re giving us an excellent look at terrain commonly overlooked by archaeological researchers.

In our area, hundreds of kilometers of fireguards made to contain the giant Elephant Hill wildfire have been surveyed, painstakingly walked by crews looking for signs of archaeological deposits.

And what we’re finding is refining how archaeologists think about precontact land use. While we usually focus our attention on residential occupation in large river valleys, we’re now finding more and more sites in all kinds of different settings, from headwaters to valley bottoms.