There are many different ways to turn a rock into a useable tool. The most commonly recognized rock tool, referred to as a lithic tool, is an arrowhead style projectile point. This lithic technology can take a considerable amount of effort, and a large rock, to create. There are many lithic tools made for quick use, which involve much less preparation, time, and effort. These are referred to as expedient tools, and one of these tools is the microblade.

In Photo 1, you can see the largest artifact in the top left - this is a microblade core. The remaining 13 artifacts are different sizes of microblades – some broken and some whole. Microblades are removed from the microblade core with a length at least 2.5 times longer than they are wide. They have parallel edges, and on one side you can see the places where previous microblades or flakes were removed, called scars. The cores exhibit long, narrow microblade scars and often are shaped like a cone. Photo 2 gives a good visual of the 4 sides of a microblade, as well as the typical ‘cone-shape’ of a microblade core.

According to research, microblades were first used in northeast Asia. The technology was brought over to North America by way of Beringia, the Bering land straight, to modern day Alaska. Dating back to 11,600 BP, evidence from Swan Point, Alaska indicates some of the first people to enter North America brough the microblade technology with them. This hypothesis is based on similarities in the methods that the microblade core is made into the individual microblades, called ‘core reduction strategy.’

After making its way into the northern end of North America, the microblade lithic technology continued to expand to the south, where it has been observed in a wide time span of archaeological contexts, covering the entire prehistoric period in British Columbia. These observations are made when microblades are found with materials or technologies which can be connected to a specific range of years.

One study looked at a number of microblade sites and their locations, and it was noted that microblades were more frequently found in higher concentrations in temporary, upland campsites. This led to their conclusion that microblade technology made for a toolkit that was flexible, versatile, and easy to adapt while moving frequently with unpredictable tool needs. It was also transportable, and much lighter than the larger rocks required to make bigger tools or arrowheads.

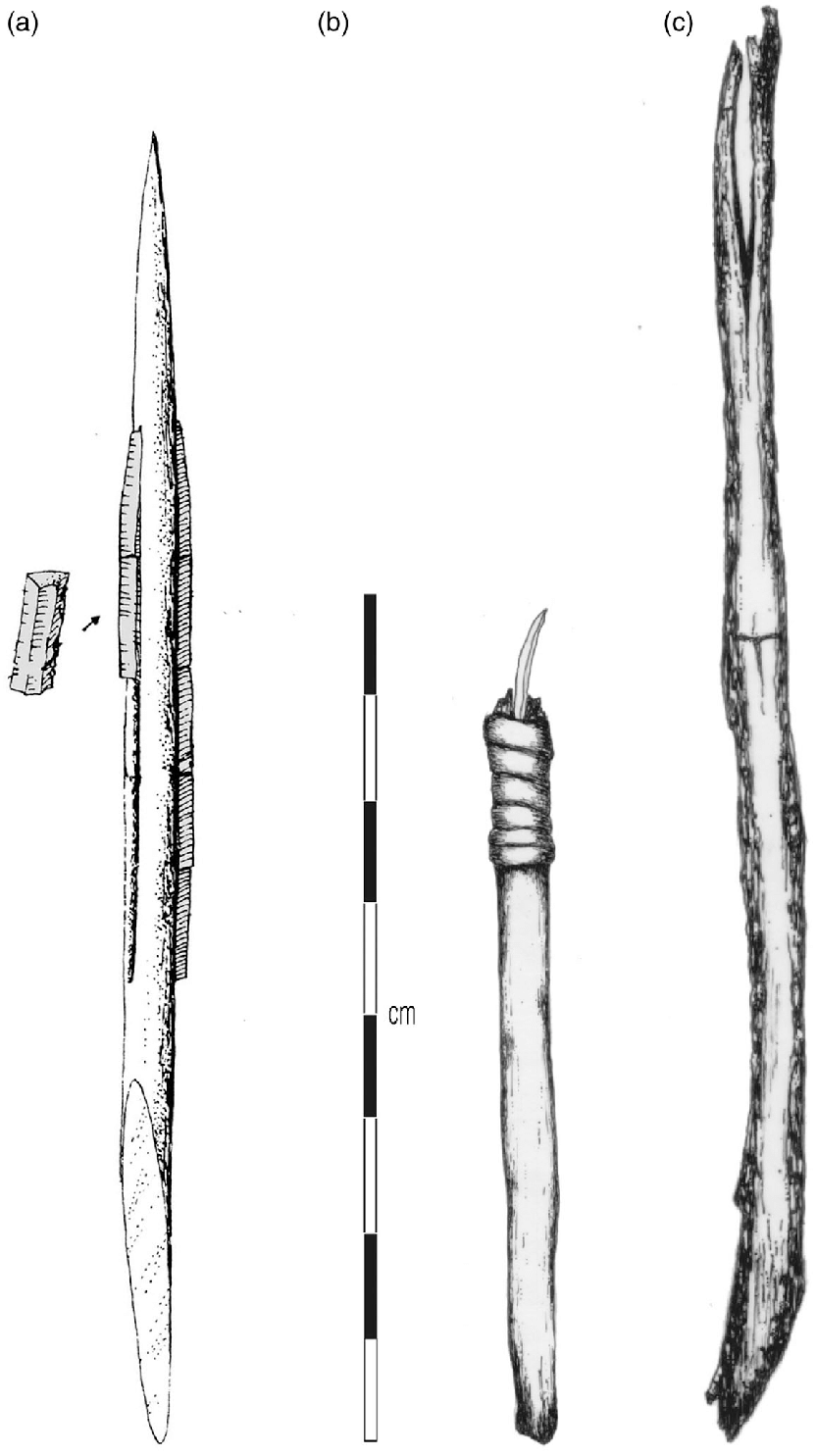

A looming question on microblades that could still use more research is what they were used for. A number of theories currently exist, and the ones shared here are by no means an exhaustive list. Microblades have been found as hafted tools, meaning they were attached to a handle made of antler, bone, or wood. At a site in Washington State where a collection of hafted microblades were recovered, both side hafted and end hafted knives were identified (Photo 3). This means that the blade was attached to the end of a handle, making it more of an engraving style tool, as well as to the side of a handle, making it into a cutting style tool.

Microblades have many attributes which make them useful in a variety of tasks. They have been observed all over British Columbia, including around the Kamloops area, and continue to be discovered as archaeological excavations continue. I was involved in an excavation this fall within an hour’s drive of Kamloops, where the crews found X3 of microblades. Analysis is currently underway, and we are excited to see how they fit into the archaeological record, and how they compare to what is already known about this fascinating technology.