I don’t recall when I first learned about culturally modified trees (CMTs), though it was quite early in my university career. I do remember that my initial opinions of the subject were dismissive, the typical hubris of a wet-behind-the ears aspiring archaeologist.

My first real exposure to them is, however, burned into my memory. I was freshly graduated from university, riding shotgun in a rattly old pickup on my way up to Campbell River on my first ever stint at forestry archaeology. At one point the highway passed through a recently logged cut block and my boss started muttering “somewhere around here...” To my distress, he stopped focusing on the driving and started looking intently out the side window at the procession of tree stumps, the truck slowly drifting back and forth across the yellow line.

Fortunately, we pulled off to the side of the road before the logging truck came around the corner. “I think they were just over there, come on!” Puzzled, I followed up into the treacherous logging slash in my decidedly unsuitable running shoes. “Here we go, climb up on this stump and look at this scar…” Thus began my initiation into the study of CMTs.

On that trip I observed several CMT types, learned how to strip cedar for basket making (creating brand-new CMTs – job security!), and became rather adept at clambering up onto slippery stumps to examine the scars revealed by logging. At the time, I just took this in stride. Later, I discovered that I had the great fortune to be apprenticed to one of the pre-eminent CMT authorities in British Columbia.

In a previous Dig It article “An Archaeology of Trees” [http://republicofarchaeology.ca/digit/2018/1/8/an-archaeology-of-trees], Joanne Hammond discusses the major CMT types found in BC and their importance as living evidence of past and present forest use by Indigenous peoples across the land. Here I would like to focus on how archaeologists approach the study of CMTs.

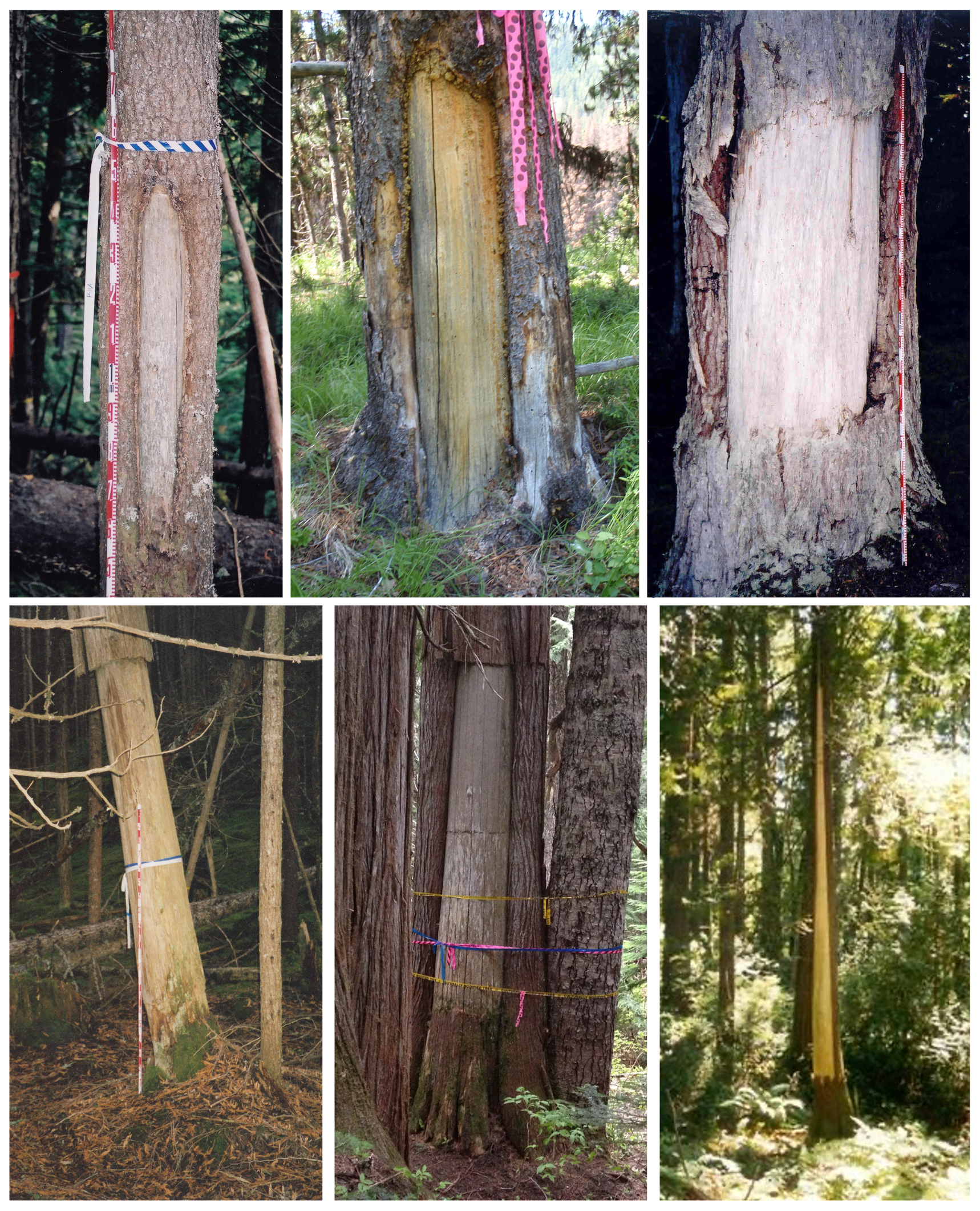

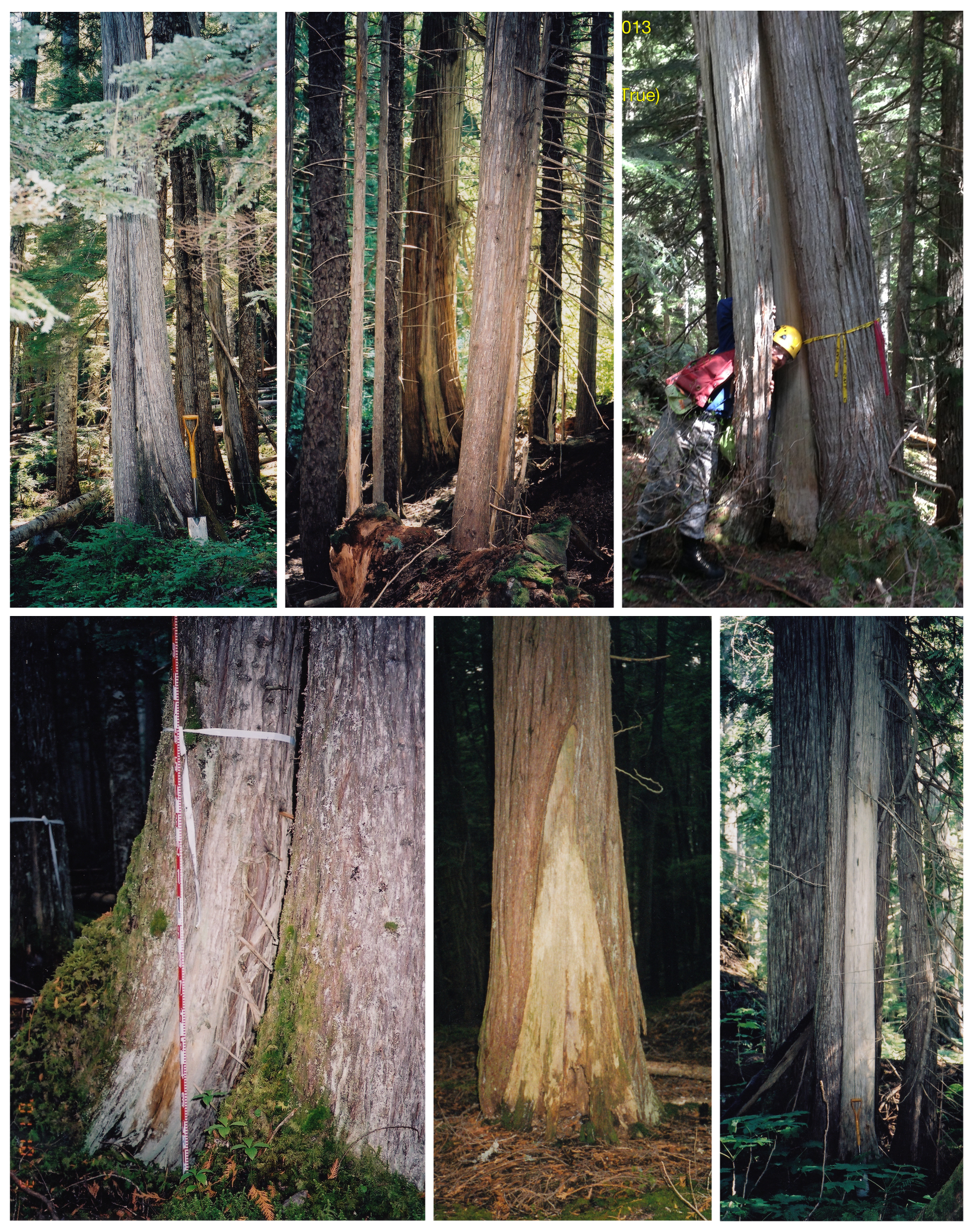

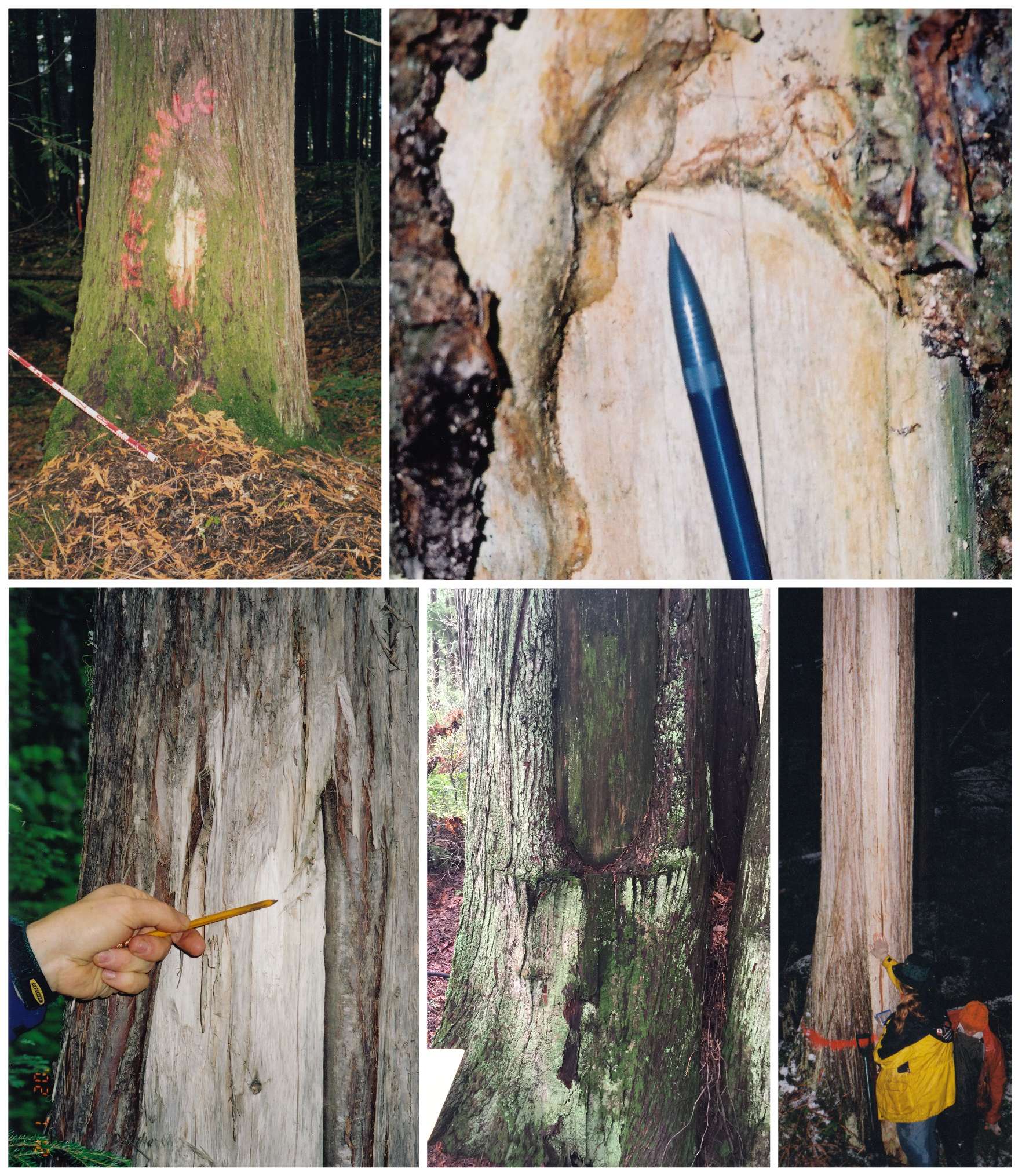

Like any other profession, on-the-job training is an important factor in archaeology. Even then, it usually references back to a solid background of university instruction. Working with CMTs is different. Though the discipline has become increasingly mainstream since the 1980s, there is still precious little useful background taught at university. Most of the instruction involves slides shows with the most obvious CMT types: standing trees with planks removed from the sides; trees with bark removed in rectangular, girdled, or triangular fashion; abandoned partially made canoes; and trees with bark removed to obtain cambium for food. The one thing these presentations generally have in common is that the pictures show lovely, unambiguous features with obvious, easy to identify crisp clear tool marks, often with helpful arrows pointing out the salient features.

If only it was this easy in the field.

Going into the forest, armed with a freshly obtained university degree, the aspiring CMT researcher quickly discovers that trees have the troubling habit of acquiring all kinds of scars, most of which are decidedly not cultural in origin. Disease, forest fire, poor growing locations, falling trees and rocks, animals, intense cold, are just a partial list of natural ways trees acquire scars. The worst part is that many of these natural scars, if left long enough, heal in ways that being to mimic CMT scars. Sometimes, when examining these ambiguous scars, the archaeologist is lucky enough to find a trace of obvious cultural origin, such as a tool mark. Alas, usually there are no easy answers so one must examine the possible CMT in its environmental context to assess the likely origin. Is the tree in an area where fire scars are present? Is there an obvious external cause such as a fallen tree that could have scraped the bark off? Is the base of the scar similar to nearby CMTs that have toolmarks visible, even if this one does not show those marks? Even though the researcher is often left with an unsatisfyingly tentative assessment of cultural vs natural origin, there is still the requirement to “make the call” and pronounce definitively that the tree scar is, or is not, a CMT.

Successful CMT researchers have several things in common. They have looked critically at many trees. So. Many. Trees. They prefer to conduct fieldwork in a collaborative fashion with others so they can “talk through” the more challenging CMT features. They are comfortable with uncertainty.

Finally, despite many fruitless hours embroiled in deep discussions about CMT identification with colleagues in small-town pubs, they all have a dream; someone, somewhere, someday, will create a simple flowchart or checklist that will allow them to easily categorize the features of a CMT and definitively allow them to make a confident determination of its cultural or natural origin.