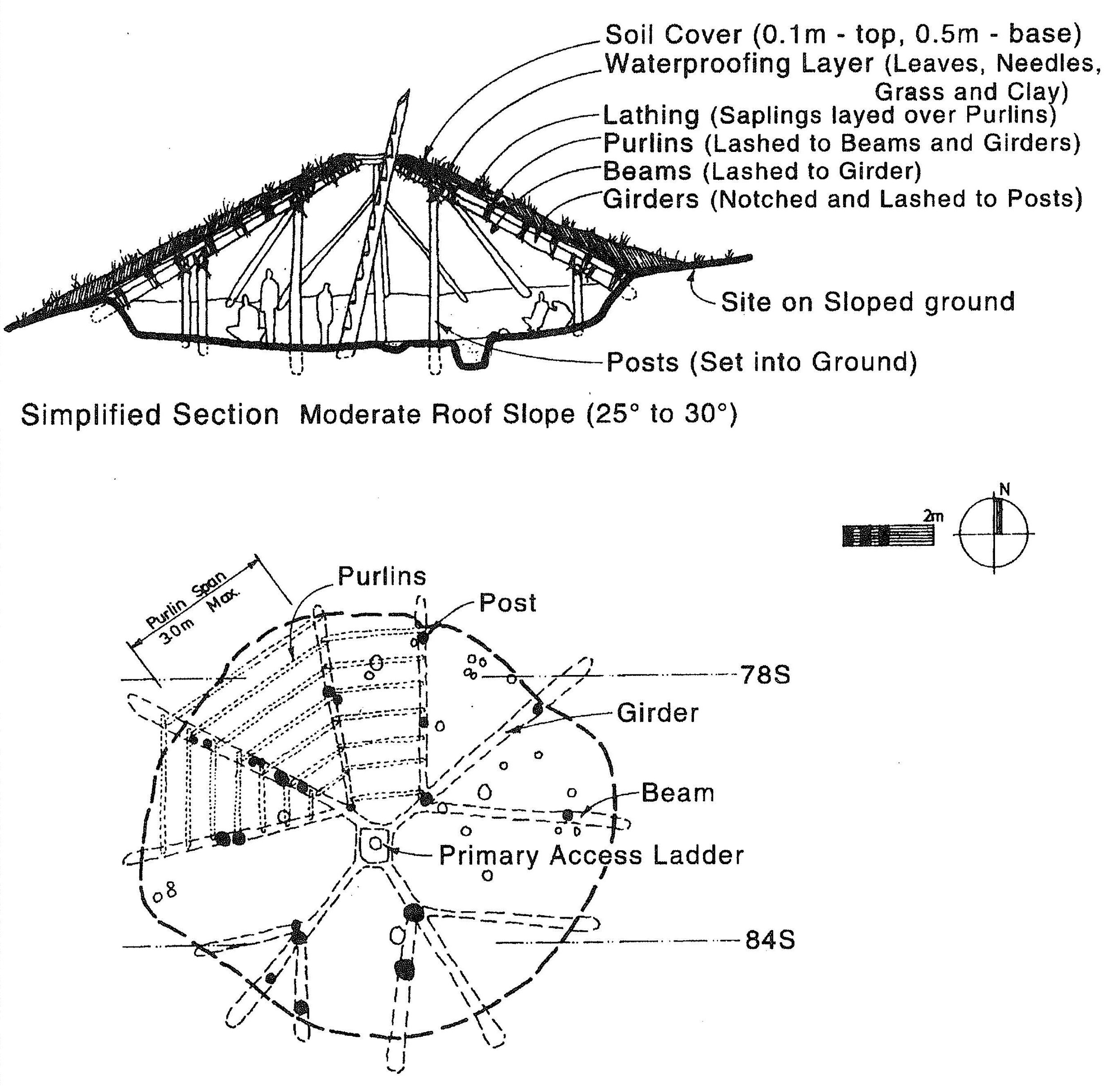

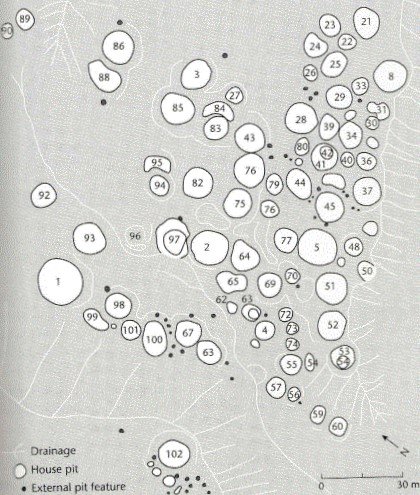

As we move toward the end of this year and into the New Year, we are all adjusting to staying at home, using foods we have stored, making crafts and keeping active with indoor hobbies. For many, this has been a change in lifestyle, but when we look at the archaeology of the Thompson and Fraser River areas, staying home during the winter months was the norm. In the Secwepemc calendar, the month of January is Pellkwetmin, meaning stay at home month. Home was the winter pithouse, organized into villages of various sizes that were distributed along the banks of rivers and lakes. Within a village, houses of different sizes raise questions among archaeologists if house size was an indication of family size and number of people within a home, or, did the size of a house indicate the status of the family. Were bigger houses a direct correlation to family wealth or status within the community? Did larger houses have different artifacts than smaller houses? How were the homes organized and did this differ based on house size? These questions have prompted years of archaeology field schools and academic research at pithouse villages on the BC plateau. The pithouse village at Keatley Creek in St’át’imc Territory is one of these well-studied villages and provides some insights to the questions asked above.

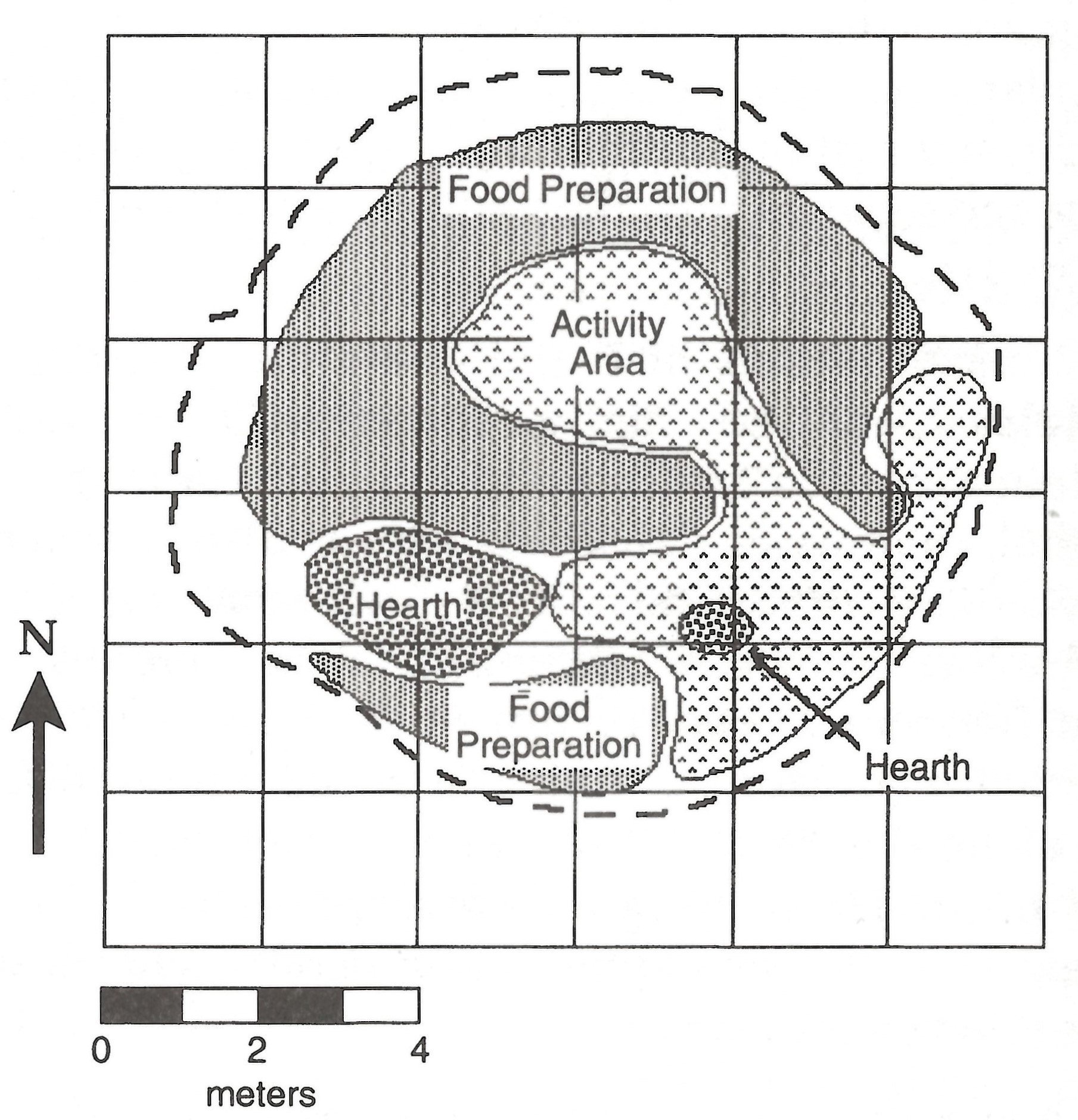

In looking at the organization of house floors at Keatley Creek, archaeologists identified patterns based on the spatial distribution of stone tools and faunal (animal) remains. These patterns were interpreted to represent activities within the house. In considering our own homes, how is the living room different than the kitchen? What ‘artifacts’ would be in each space? One of the ways to test observed patterns of artifacts and interpretations of how households were organized is to looks at soil chemistry from samples taken from the living floors of houses to distinguish between activity areas, such as: cooking, living, or sleeping areas. By analyzing soil samples, a comparison can be made between unmodified soils and soils modified by humans, where humans have occupied an area for long enough to create a new soil that is chemically distinct from undisturbed soils. Higher or lower concentrations of elements such as calcium, phosphorus, strontium, and potassium can be indicators of how a house may have been spatially organized. For example, phosphorus and potassium are indicators of ash and hearths (fire pits) while concentrations of phosphorus, calcium, and strontium can indicate areas used for food preparation and the combination of calcium and strontium is associated with a ‘general activity’ area. By recognizing chemically distinct soils throughout the house and combining that with the distribution of artifacts, archaeologists can be more accurate in reconstructing the use of space for a kitchen versus a living area. Since houses were occupied over many years, archaeologists can also analyse soils from different time periods within the house to determine if the interior space was used differently.

As you move about your house, consider what information you are leaving behind for future archaeologists to study.

Alysha Edwards is an Indigenous archaeologist based in Lillooet. Nadine Gray is a Kamloops based archaeologist and instructor at TRU.